Welcome to SJGLE.com! |Register for free|log in

Welcome to SJGLE.com! |Register for free|log in

Related Searches: Tea Vitamin Nutrients Ingredients paper cup packing

In Israel, a snack called Bamba is credited for a dramatically lower rate of peanut allergy among children.

The morsels of puffed corn resemble Cheetos, except taste like peanut butter. Americans can now buy them in Trader Joes.

The idea is that Israeli children are introduced to peanut-based foods at much earlier ages, and that may help kids develop protection from development of peanut allergy. Researchers confirmed that hypothesis in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2015.

Now, drug companies are seeking to replicate that approach through medicine. Aimmune and DBV Technologies both aim to file for approval of therapies this year that seek to retrain the immune system so it doesnt overreact to peanuts. Both are examples of the new approaches to preventing potentially life-threatening reactions.

"Its a huge problem," said Robert W. Baird analyst Brian Skorney, "Sending kids to school, theyre not allowed to bring any peanut-based food because theres almost always at least one kid in class with peanut allergy."

Public health data support what many parents observe: the prevalence of food allergies, the most common cause of severe reactions known as anaphylaxis, increased by 70 percent in U.S. kids younger than 18 between 1997 and 2016.

Hospital claims for severe allergy reactions have increased, too, by 377 percent from 2007 to 2016, according to a study from FAIR Health.

Researchers cite a handful of potential contributors for the rise in allergies: parents reluctance to introduce foods like peanuts too early; the "hygiene hypothesis," the idea that were so clean that our immune systems have too little to do and thus overreact to innocuous stimuli; and that our microbiomes, or gut bacteria, may be out of whack.

"We dont quite have the answer yet," said Dr. Julie Wang, professor of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. "Those are areas of active investigation."

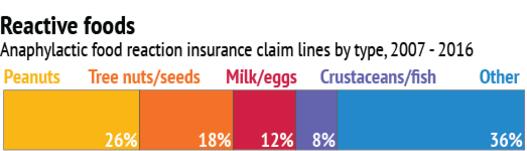

Of all the allergy offenders, peanuts are the worst — at least in terms of the number of people they send to the hospital.

Will Brody, a 13-year-old eighth grader in New York City, knows that firsthand. He had his first reaction when he was a year old, and developed allergies to tree nuts as well. Hes had to use an EpiPen four times to counteract severe reactions.

"One particular episode that I recall, he said: My throat is closing, Mom, Im having trouble breathing, I just dont want to die," Wills mom, Joanna Brody, told CNBC.

"I was really scared," Will added.

So hes trying the Bamba approach – only hes doing it through a clinical trial of a product developed by Aimmune.

Building a tolerance

Every night, Will mixes a packet of peanut powder into his food. Gradually, the dose increases. The idea: establish a tolerance to peanuts over time so that accidental exposure wont have dire consequences.

"In the beginning, they start you on a very low dose, one one-hundredth of a peanut," Joanna said. Every two weeks, the dose increased, while Will was monitored in the doctors office. "By the end, this past August when they did their last food challenge, he was able to complete the entire challenge."

Will could tolerate more than 4,000 milligrams of peanut powder, Joanna said, "which is something like 13 peanuts."

Dr. Jayson Dallas, Aimmunes chief executive, says a majority of kids in the trial could tolerate at least four peanuts by the end.

"If we treated 10 children, we could get eight of those children through the treatment process and essentially protected from accidental exposure to peanuts out there in the real world."

Not everyone made it through, though, and thats because of side effects related to the treatment itself: patients are ingesting the very thing theyre allergic to.

"At first we almost didnt do it because it was like eating the thing that I was avoiding at all costs for my whole life," said Will. Occasional stomach aches are the worst side effect, he said.

The up-dosing process takes six months, and patients then stay on a maintenance dose equivalent to about one peanut a day.

Aimmune plans to file for regulatory approval by the end of this year. If its successful, Bairds Skorney estimates the therapy could draw peak sales in 2025 of $1.3 billion worldwide.

Its not the only new treatment in development, though. On almost a parallel track is French biotech DBV Technologies. It too, delivers a small amount of peanut protein each day, but its treatment has a few significant differences.

First is the delivery method: DBVs therapy is administered with a patch thats worn on the childs back. Next is the dose: Every day, patients are administered the equivalent of one one-thousandth of a peanut via the patch, which is called Viaskin. The dose doesnt increase the way Aimmunes does.

"It slowly desensitizes the child over time," Kevin Trapp, DBVs chief commercial officer, "The child is getting about a peanut over three years."

What kind of protection does that translate into? In late-stage clinical trial results reported last October, DBV found that patients treated with Viaskin could tolerate an average of 900 milligrams of peanut protein after 12 months, compared with 360 milligrams for those on placebo. The study didnt meet its primary statistical goal, however: a difference in response rates between the active and placebo arms.

Nonetheless, DBV also plans to file for regulatory approval by the end of this year, Trapp said. He notes the therapy is well-tolerated, with some skin reactions wher the patch adheres as the main side effects.

Skorney says the choice between Aimmunes and DBVs treatments may come down to efficacy versus tolerability.

"When we talk to physicians and families, theres this gravitation toward Viaskin just in terms of: this is so easy, you just put it on your kid and dont have to worry too much; youre not going through the cumbersome and sometimes intolerable step-up process" that Aimmunes treatment requires, Skorney explained. "But I think you lose some efficacy because of that more modest approach."

Hes more bullish on Aimmunes prospects.

"One of the things I like about Aimmune is you walk out of the physicians office knowing how much your kid can tolerate," Skorney said. "The data for Aimmune is much clearer; theres much more of a magnitude of benefit."

Targeting the allergen

Smaller biotech companies arent the only ones working on new approaches to allergy; biotech giant Regeneron is also making a major push into the field, led by its recently approved medicine, Dupixent.

The drug targets two signaling molecules, interleukin 4 and interleukin 13, found to be overactive in allergic diseases like atopic dermatitis and asthma, explained Regenerons president and chief scientific officer, Dr. George Yancopoulos.

"It turns out the more specifically you can identify whats wrong with the immune system and whats overactive, you can target only that," Yancopoulos told CNBC in an interview. "This is the definition of precision medicine," a strategy not often embraced in immune diseases, which he said have been dominated by a more "nuclear approach" using steroids or general immunosuppressants.

The companys also testing Dupixent in combination with Aimmunes peanut allergy treatment. But its approach to allergy doesnt stop there.

"Can we target the allergen itself?" Jamie Orengo, Regenerons director of immunology and inflammation, said in an interview. "We try to develop antibodies that are specific for allergens, so that we can prevent them from even initiating a response."

In other words, Regeneron is working on determining what it is about cats, or pollen, or peanuts, that triggers allergic reactions, and is developing medicines to block those molecules from irritating the immune system.

"We know what the major driver is from the cat allergen thats inducing a lot of the symptoms, and we demonstrated this pre-clinically in these labs," Orengo said. "Then we actually took it into a phase 1 clinical study and showed that patients do have symptomatic relief for their cat allergy."

How do you test that? Put subjects into a room, and pipe cat dander through the air vents. They call it a "cat room."

For Orengo, the work is personal. Her three young sons all have asthma and severe allergies.

"I see how much this affects my children; they know Im in science and they know that Im working on allergy drugs and asthma drugs, and they ask me all the time when are these things going to be available — when are these things going to help us?" Orengo reflected. "It definitely puts a spark in everything that you do."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Editors Note:

To apply for becoming a contributor of EN-SJGLE.com,

welcome to send your CV and sample works to us,

Email: Julia.Zhang@ubmsinoexpo.com.

E-newsletter

Tags